Learning physics without units

Our approach identifies optimal unit-free physical variables by generalizing the traditional π theorem

Scientific discovery searches for universality, parsimony and invariance. In a world of complexity, we look for common and simple rules that apply to everything from a drop of water to the ocean. Dimensional analysis is the essential tool in this quest. It allows us to strip away units of measurement to reveal the dimensionless variables that govern how a system truly behaves.

For over a century, the Buckingham-π theorem has been the cornerstone of the dimensional analysis, providing the mathematical recipe for discovering these essential dimensionless variables. However, the traditional theorem has a shortcoming: it is a rule of existence, not a rule of selection. While it tells us the existence of the dimensionless variables, it offers no guidance on which specific combinations are the most parsimonious. In complex, modern datasets where dozens of variables interact, the traditional approach often leaves scientists guessing which dimensionless variables truly capture the underlying physical laws.

In a paper, we introduce a new method to discover the most important dimensionless variables directly from data. The code is available in the GitHub repository.

Unit-free learning for universal prediction

In physics, the same law applies to systems at vastly different scales. However, machine learning techniques that appear to learn laws at one scale often fail when applied to another. Because these models are unit-based, they treat changes in scale as an extrapolation into unknown region. By focusing on dimensionless variables, we ensure that the model learns the scale-invariance laws. This allows the physics discovered in a small-scale experiment to remain predictive at much larger scales.

Parsimonious discovery of variables

The Buckingham-π theorem often overestimates the number of dimensionless variables required to describe a system. It provides a mathematical list of what could matter, but in reality, many of these groups are redundant or physically negligible. The cost of this overestimation is staggering. If the traditional theorem suggests 7 dimensionless variables and you need 10 measurements per variable to build a reliable model, you would require 10^7 (10 million) experiments. However, if our method can reduce those 7 variables down to the 2 most dominant ones, we only require 10^2 experiments.

Our perspective: Identify optimal variable using information theory

We introduce IT-π, a model-free method that combines dimensionless learning with the principles of information theory. Our approach is grounded in the information-theoretic irreducible error theorem. The key insight is that prediction accuracy of any model is fundamentally limited by the amount of information the input contains about the output, where information here is defined within the framework of information theory.

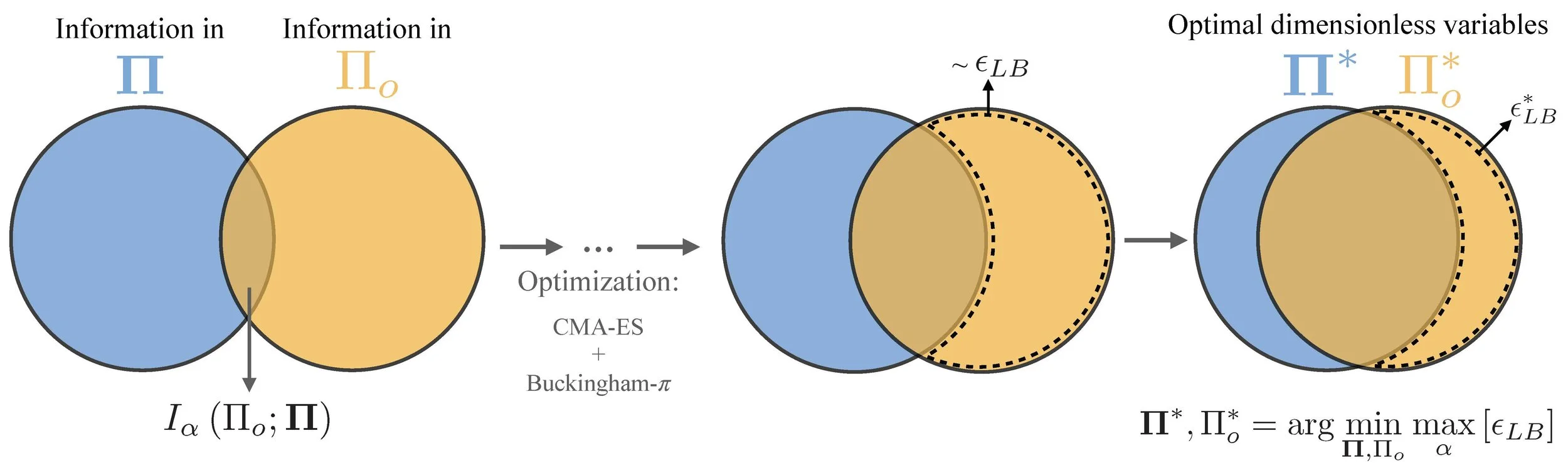

The optimal dimensionless inputs and dimensionless output are those minimizing the irreducible error.

Circles represent the information content of the dimensionless input Π and output Πo. The overlapping region denotes their mutual information of order α, Iα(Πo; Π). The area enclosed by the dashed line corresponds to the amount of information in Πo that cannot be inferred from Π, which is related to the irreducible error. The optimization proceeds from left to right, evaluating candidate pairs of input and ouput to minimize irreducible error until the optimal value irreducible error is reached. The candidates are constrained to be dimensionless by the Buckingham-π theorem.

Example: Dimensionless learning in turbulence

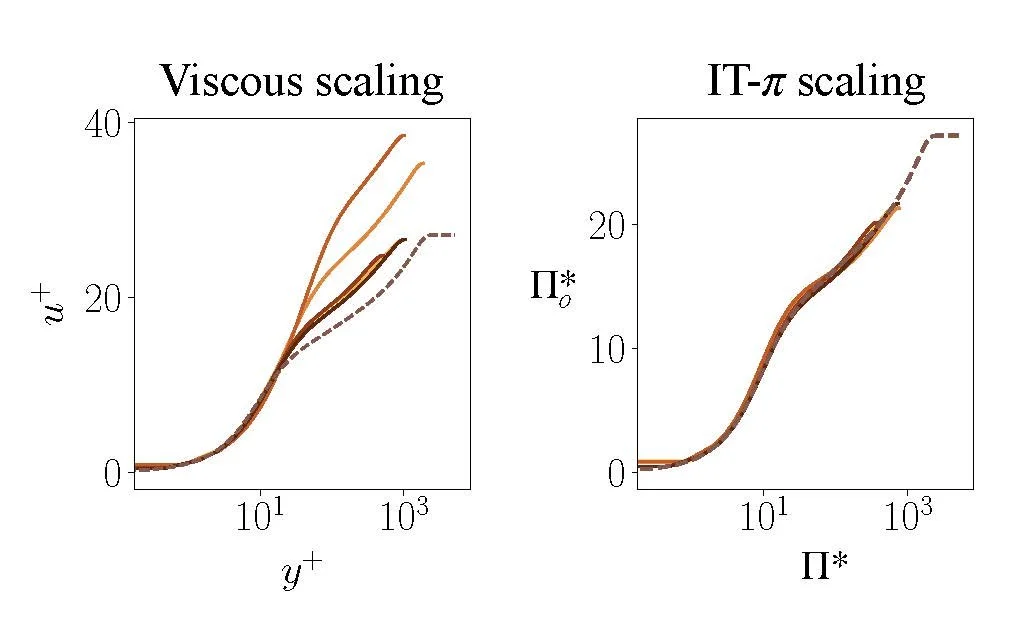

We discover a local scaling for the mean velocity profile in compressible turbulent channels using high-fidelity simulation data from existing literature. The dataset, which spans different Reynolds and Mach numbers, includes the mean velocity and the flow state. The scaling identified by IT-π improves the collapse of the compressible velocity profiles across the range of Mach and Reynolds numbers considered compared to the classic viscous scaling. A closer inspection of the dimensionless input and output variables reveals that this improvement is accomplished by accounting for local variations in density and viscosity.

Velocity scaling for compressible turbulence. Solid lines of different colors represent velocity profiles at various Mach and Reynolds numbers; the dashed line corresponds to the incompressible turbulence velocity profile. Left hand: Viscous velocity profile u+ versus y+. Right hand: Dimensionless velocity profile obtained using IT-π scaling.